Optimism vs Pessimism

Do we live in a Good Universe with evil stripes, or an Evil Universe with good stripes?

To be optimistic or pessimistic, that is the question. Or to paraphrase the question that children ask about zebras, is ours a good Universe with evil stripes, or an evil Universe with good stripes?

What makes this question really difficult is, it cannot be answered by the intellect; it can be answered only by the heart, and so much of our postmodern culture functions as if it was intentionally designed to alienate us from ourselves, to cause us to become “men without chests” (to use a phrase from C.S. Lewis). To borrow a metaphor from Jonathan Heidt for conscious vs subconscious desire, the conscious mind is like a rider atop an elephant; it doesn’t matter if the rider is optimistic about where he wants to go, what really matters is how the elephant feels. The rider can lie to himself with charts and graphs showing the all-important line going up and up and up, but if the elephant feels deep down that the charts and graphs are all bullshit (which they increasingly are), the rider isn’t going anywhere.

I think this is one way of making sense of the warning in the Letter of James about seeking wisdom with a divided mind:

If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given him. But let him ask in faith, with no doubting, for the one who doubts is like a wave of the sea that is driven and tossed by the wind. For that person must not suppose that he will receive anything from the Lord; he is a double-minded man, unstable in all his ways. James 1: 5-8 (ESV).

Despite what Hamlet says, optimism vs pessimism really is the fundamental question, because if you’re optimistic — if you believe the ultimate sovereign over your existence is a good God rather than an evil one — then you already have your answer to the question of whether it is better to be or not to be. “Count no man happy, until the end is known,” warned Solon. If you really believe that the ultimate reality is Good, that “all things work together for the good to them that love God, to them who are called according to his purpose” (Romans 8: 28 (KJV)), then you would always and automatically choose to be. You would cherish your own life and make the most of it; you would have children and raise a family; and you would gladly sacrifice short term comforts and pleasures in pursuit of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful, because you would be confident that the ultimate God (and the good powers aligned with the ultimate God) would bless you in your quest. But in order for you to really believe, the elephant has to be convinced as well.

By nature, I am predisposed towards pessimism, towards seeing problems more clearly than blessings, and towards focusing on threats rather than opportunities. Experience has taught me the problem with this kind of pessimism: being ungrateful for blessings, being so distracted by problems and potential threats that I miss opportunities, complaining and engaging in negative conversations about what’s wrong with the world, rather than talking about what’s right, etc.

Of course, part of the problem is that pessimism is easy to justify. The evil powers are ascendant in our world. Our civilization is infected with their pathologies at the highest levels — for example, the UK government importing, enabling, and protecting Pakistani Muslim rape gangs preying upon the children of the native population, partly because the ruling class are true believers in DIEversity (they just refuse to pay for their luxury beliefs and pass 100% of the costs onto the regular people), but probably mostly because the British ruling class have their own pedophilia problems (see, e.g., Jimmy Saville and his enablers) and the devil knows his own. I don’t know why the Evil Power is the god of this world, but they/them (using the devil’s preferred pronouns) is obviously worshiped and obeyed by those at the highest levels of society. Maybe this is because after being set up in a good world that the good God made, ancient Man made a Faustian bargain with a demonic interloper, in which Man sold himself and his posterity into bondage (as Orthodox Christianity teaches). Or maybe the Orthodox cosmology and biblical timeline are correct, but we got “left behind” and are now living in a post-millennial age of satanic deception described in Revelations 20: 1-10. Or maybe the Evil Power created this world, so that they/them could feel like gods; but because they/them is an uncreative parasite, they/them simply made a bad counterfeit of a higher realm created by the real God; and to feel more godlike, they/them tricked us (at least those of us who have souls and are not NPC/hylics) into entering their simulacrum (as Gnostics may believe). Or maybe the Mind of God considers every possible world in the process of creating the best one and we are divine sparks providing experiential data from the perspective of life in this possible world; the Mind of God is beyond the temporal dimensions of our world, so that even though we experience being within the timeline of this world, in God’s ultimate Reality (which is outside of this world’s timeline), we are already with God in Christ in the best of all possible worlds, i.e., “heaven.” (See, Ephesians 2: 6.) I suppose there are any number of possibilities, given the Rorschach Test that is our conscious experience of life in this world, and the flaws and gaps in our epistemology. Regardless of how or why, the upshot of all of this is: Evil is real, and the power of Evil in our world is real, so pessimism is easy to justify — it just requires a spiritual framing or orientation that posits this world as the ultimate reality, and the powers that govern our world as the ultimate power.

C.S. Lewis provides the clearest and most succinct argument against this framing in the opening chapters of Mere Christianity (something I previously wrote about in my post The Good that Evil Does). Here is an excerpt from Lewis:

[T]his Bad Power, who is supposed to be on an equal footing with the Good Power, and to love badness in the same way as the Good Power loves goodness, is a mere bogy. In order to be bad he must have good things to want and then to pursue in the wrong way: he must have impulses which were originally good in order to be able to pervert them. But if he is bad he cannot supply himself either with good things to desire or with good impulses to pervert. He must be getting both from the Good Power. And if so, then he is not independent. He is part of the Good Power’s world: he was made either by the Good Power or by some power above them both . . . To be bad, he must exist and have intelligence and will. But existence, intelligence and will are in themselves good. Therefore he must be getting them from the Good Power: even to be bad he must borrow or steal from his opponent . . . Evil is a parasite, not an original thing.1

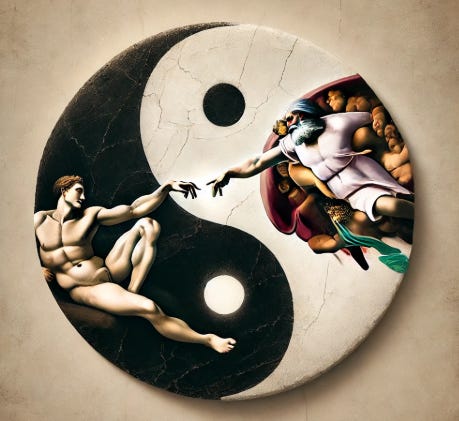

But suppose that Dualism is correct and the Good Power and the Evil Power are independent and coeternal, such that either could be considered to have an equally valid claim to be “the real God.” (Lewis considers this possibility and rejects it in Mere Christianity, and his argument is dispositive in my view, but suppose that Lewis is wrong.) Suppose that instead of a Good Universe with Evil stripes or an Evil Universe with Good stripes, there are only Good and Evil stripes? Suppose that we are living on the razors edge where a Good and Evil stripe meet, or that we inhabit the white dot in the middle of the black half of the Yin-Yang symbol, and the Good God, whose realm is the light half, is reaching out to us? Suppose that we ourselves are divided beings, composed of parts drawn from the Darkness and the Light? In that case, we are in a position analogous to the Existentialist dilemma articulated by Sartre in Existentialism is a Humanism, and the question before us is, which side of our own divided nature do we wish to posit as the root of our being and the guiding star of our ethics? Which of the two Powers do we wish to worship as God? We must choose. We can go either way, and regardless of the decision we make, we can rationalize it afterwards with equally persuasive Logic. The question is really pre-logical or a priori, because our answer determines which premises we see as sound and which arguments we see as valid. Unless there is a self-evident reason for choosing Good over Evil (I think there is, but of course one cannot prove that something is self-evident; one can only see it), then we are at a place in the valley between equipollent alternative timelines leading in opposite directions.

Intuition and insight are magical, almost mystical. Where do our ideas come from? Do we have ideas, or do ideas have us? What are the natures and origins of the Muses that inspire our artistic visions? Think of the keys on a saxophone: depressing or releasing the keys redirects the flow of air, which in turn determines which sound is created. Are we more like the keys, and various spiritual forces flow through us like the air flowing through a saxophone? Or are we more like the air, being directed this way or that by divine beings in order to create a harmonious — or disharmonious — sound? Perhaps it is both/and. Perhaps we are the keys, the flow of breath, and the saxophone itself, and perhaps there are two conductors on opposite stages directing melodies that are at odds with each other, and perhaps our world is full of some people following one conductor, some following the other conductor, some alternating between following one and then the other, and some ignoring both conductors and either playing their own tune or refusing to play altogether. Suppose we are able to choose which conductor to follow, and once we have chosen our conductor, we are then able to move towards that conductor’s platform and conscientiously surround ourselves with others who have made the same choice. I believe “as above, so below” is a true insight, and I think it is also just as true to say “as within, so without.” Which causes which is not always clear, and it is entirely possible that both are manifestations of a more fundamental cause than that which we can consciously conceive with the egoic mind. In the Symphony of Being, sound is Life and silence is Death, but both sound and silence are part of the same higher reality of song. Which song will we be a part of? Which conductor will we choose to follow?

One night, on the dreamlike borderland between wakefulness and sleep, I was asked a question: If you can choose between two different framings, and if Logic lends herself equally towards rationalizing either framing, then why not choose the framing that is most beneficial?

This question, and the way it was asked, reminded me of the way the Ancients used to “do” philosophy. They did not delude themselves into thinking that mere intellectual investigations could arrive conclusively at the Truth. Instead, they simply posited their philosophical framing and first principles and then developed a method for living well in accordance with that. They developed communities and schools with practical ends in mind: how to live well.

In the case of Optimism vs Pessimism, which are the two framings? Option one: the Good Power is our God. We live in a Good Universe with evil stripes; The Good is the fundamental and ultimate Reality. Bad happens, within the evil stripes, but the Good Power is an alchemist who can take what the Evil Power intends for harm and turn it to Good. So why not choose the Good Power, and participate in Christ’s mission to instantiate and promote the Good, the True, and the Beautiful? Or option two: the Evil Power is our God. We live in an Evil Universe with good stripes; Evil is the fundamental and ultimate Reality. Good happens, within the good stripes, but the Evil Power is a cunning tormenter, able to use these limited and ephemeral goods to lead us on with false hopes before cruelly yanking the rug out from under our feet and crushing us with continual reminders that our best efforts will ultimately fail, so why not curse the Good Power and die? Or if we wish to be predator rather than prey, why not join the Evil Power and delight ourselves in stealing, killing, and destroying? These two framings are each paths leading in opposite directions. Many of us are too wishy-washy to choose, so we become playthings of fate, getting pushed and pulled this way and that, like “sheep without a shepherd.”

Now, the question of Optimism vs Pessimism is often obscured by a deceptive framing (the Evil Power’s chief weapon is deception). Naive and willful ignorance and delusional denialism are celebrated as “optimism,” but true optimism is a virtue, not a vice.

In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle articulated some incredibly helpful insights: Virtue is the mean between opposite vices; by nature, each of us is predisposed towards one vicious extreme or the other; developing a good character consists of cultivating the capacity (as a second nature) of choosing the virtuous mean (i.e., what is appropriate, good, and honorable) in each circumstance; because we don’t reliably know what is appropriate until we have already developed such a character, the most pragmatic program for us to follow is for us to conscientiously do the opposite of what we know our vicious default to be; and if we do this often enough, while also seeking to learn from and imitate the actions of good and honorable people, we will make mistakes, but we will also have moments of real insight and will develop our own capacity for recognizing and practicing moral goodness. If we follow this regimen consistently over time, we will develop a virtuous character.

With that in mind, consider once more the question of Optimism vs Pessimism, in light of the way “optimism” is popularly understood. On one vicious extreme, you have a person who is convinced that the ultimate reality is evil and suffering, but what inevitably happens when he lives this way? Depression, anxiety, resentment, frustration, anger, and as these states of mind grow like a cancer upon his soul and he sees himself locked into a primal war of all against all, the decision of whether to become predator, prey, or parasite becomes inescapable. On the other vicious extreme, you have a person who is like Dr. Pangloss in Candide, proclaiming a naive fantasy where evil is rationalized away and ignored, rather than confronted and conquered; he lives a life of delusional avoidance, of feel-good platitudes that are only believable in a bubble of First World prosperity and safety. You know which of these vicious extremes you’re drawn to by default. The Virtuous Way, like the Dao, cannot be defined, but by conscientiously following Aristotle’s method of choosing a response to Life’s challenges that is opposed to your own vicious default, and by conscientiously imitating the examples of good and honorable people, you can catch glimpses of the Virtuous Way and embody the virtuous character traits as a “second nature.”

I know that my own default is towards pessimism, so I have tried to embrace the opposite. I have failed and fallen back into my old ways many times. I have sometimes imposed upon myself an opposite delusion of “positive thinking,” and because that too is a delusion, it has not been sustainable. However, I have managed to enjoy some progress in this endeavor and have occasionally caught glimpses of deeper and more virtuous reality. “Progress, not perfection.” I am a long way from where I ought to be, but I am a long way from where I was.

To return to the metaphor of the competing conductors, as I conscientiously sought to follow the optimistic conductor, rather than the pessimistic one that I’d been following by default, I sometimes managed to “tune into” a song being directed by a conductor who is higher than either of them, and this higher conductor manages to incorporate, into his own song, notes from the competing performances of the two opposite composers below him. In those fleeting moments of hearing that higher melody, I remembered those moments of beauty in the otherwise vicious songs being directed by the vicious conductors in our fallen world, and I understood that this beauty came, not from them, but from the higher conductor who sometimes uses them to get the attention of those who are enamored of these lower performances. Imagine a battle of the bands where two bands are butchering the same song simultaneously, but because they are so bad, it’s not always clear what song they are attempting to play; and then imagine the composer and original performer of that song in relation to the two terrible bands you are watching perform. There are many metaphors and symbols that convey some limited aspect of this reality, but there is no way to describe it directly (and I know I am describing it awkwardly). You have either seen it or you haven’t.

I have considered this matter from my own perspective, as someone who is by nature drawn to the vicious extreme of pessimism, but who has sought to conscientiously implement the opposite (while considering the example of good and honorable men), and who has thereby been occasionally able to apprehend the virtuous mean. But what would all of this look like for someone with the opposite vicious inclination, a naive and delusional optimist like Dr. Pangloss (or perhaps Candide)? Joy is good, but pleasant feelings based on willful ignorance and self-deception are not, and the latter is what I’m talking about here. I suppose the biblical counsel in Ecclesiastes is appropriate for such a person:

It is better to go to the house of mourning than to go to the house of feasting, for this is the end of all mankind, and the living will lay it to heart. Sorrow is better than laughter, for by sadness of face the heart is made glad. The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning, but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth. It is better for a man to hear the rebuke of the wise than to hear the song of fools. Ecclesiastes 7:2-5 (ESV).

Ultimately, the virtuous mean is the thing to seek. This ideal is conveyed in the Gospel of John through the Person of Christ:

In him was life, and the life was the light of men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it . . . He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world did not know him. He came to his own, and his own people did not receive him. But to all who did receive him, who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God, who were born, not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God. John 1:4-13 (ESV).

Jesus on his part did not entrust himself to them, because he knew all people and needed no one to bear witness about man, for he himself knew what was in man. John 2: 24-25 (ESV).

Truly, truly, I say to you, unless one is born of water and the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh, and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit. John 3: 5-6 (ESV).

The thief comes only to steal and kill and destroy. I have come that they may have life and have it abundantly. John 10:10 (ESV).

These things I have spoken unto you, that in me ye might have peace. In the world ye shall have tribulation: but be of good cheer; I have overcome the world. John 16:33 (KJV).

Christ is the ideal, because he does not deny or ignore the reality of evil, but instead confronts and conquers it through the Power of God that flows through him like an electrical current flowing through a completed circuit.

Back to the metaphor of the rider and the elephant: the rider cannot force the elephant to adopt a virtuous optimism (Faith, Hope, and Love), Christ alone has the power to do that. The Good News is, though, when the rider has determined to worship the Good Power as the Real God, Christ will show up in unexpected ways, and both elephant and rider will have transformative encounters with the living Christ. It is a process, sometimes taking us through the valley of the shadow of death, but the Real God is more real than the shadows trying to destroy us (or trying to manipulate us into destroying ourselves). This is not to deny the reality of Evil, but rather to affirm the greater reality of Good.

To be in harmony with the Good God, or to be in disharmony along with the evil god, *that* is the question.

In Mere Christianity, the premises for this argument are established throughout the first part, Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe, and Lewis makes the argument explicitly in the first two chapters of the second part, What Christians Believe, as a critique of pantheism and dualism.

If modern pessimism was rational or consistent I would have littler quarrel with it... but it's a kind of targeted pessimism combined with this strange utopianism and naivete. It's a new kind of worldview, one which I suspect is only possible in a society as comfortable and neurotic as ours...

Great essay