The Good that Evil Does

When there are no serious problems, we tend not to ask important questions . . .

“So what’s your philosophy?” is an odd question — odd because I have never known how to answer it. Usually, when someone asks you for “your philosophy,” they are asking you for a coherent set of affirmative answers about how to achieve success and derive a sense of purpose in one’s life. Unfortunately, few modern philosophers have even attempted anything remotely like this (preferring instead to play silly word games with each other). Even the Ancients, who did attempt such answers, and who came nearer to providing them than anyone in the modern era, were usually at their best when they were asking questions, rather than stating their conclusions.

The Tao that can be named is not the real Tao . . .

— The Tao Te Ching

I don’t get asked for “my philosophy” nearly as much now as I did when I was younger. I’m sure this is because, at my current stage in Life, I have far fewer random philosophical conversations with people I’ve just recently met, than I did when I was in my teens and twenties. But if someone were to ask me for “my philosophy” now, I doubt I could give a satisfactory response. When it comes to definitive answers, I have far fewer now than I used to think that I had, and the answers that I do have are nearly impossible to articulate: probably the best I could do would be to tell stories and share analogies and use word pictures and pose hypothetical “thought experiments,” and then hope that my interlocutor would be able to see some signs of the deeper Reality that I’m pointing towards — a deeper Reality that I hardly understand myself, but which I, in my best moments, have managed to catch glimpses of. However, unless the other person has already tilled this soil himself, has already reflected on these themes in light of his own lived experience, has already engaged with great thinkers who have raised these questions and attempted to answer them, unless all of these pre-conditions are already met, then I am unlikely to succeed in helping him see what I’m trying to point him towards. Worse than that, my glimpses of Reality are still mixed up with the confusion and chaos of this world’s deceptions, so that I am not yet able to reliably discern what is True and Good, let alone serve as a competent guide for anyone else.

Tao is obscured when men understand only one of a pair of opposites, or concentrate only on a partial aspect of being. Then clear expression also becomes muddled by mere word-play, affirming this one aspect and denying all the rest.

— Chuang Tzu (translated by Thomas Merton)

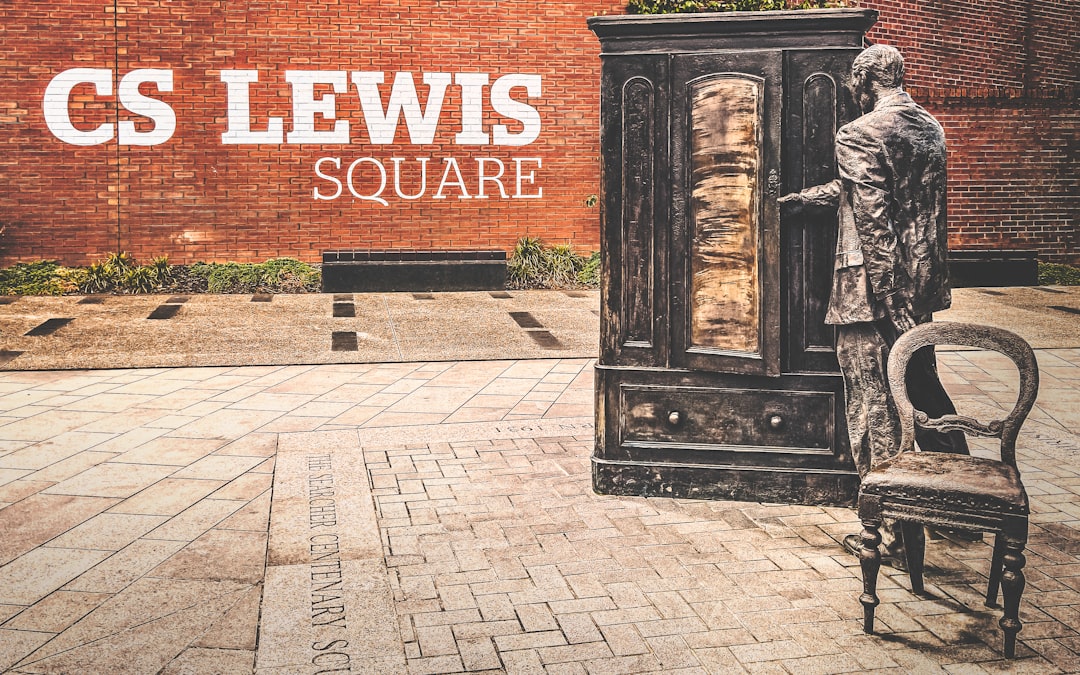

One recent thinker who remains well worth reading on these big-picture issues is C.S. Lewis. I recently reread Mere Christianity, and I am even more impressed by Lewis now than ever. I know I should avoid making categorical pronouncements, given my relative ignorance, but I will go ahead and venture this one anyway: in the past 100 years, no one has matched Lewis’s ability to articulate Life’s most fundamental issues and what those issues mean. Even if you disagree with his answers, he formulated the questions and identified the relevant issues better than anyone. Most public intellectuals completely miss the forest for the trees; some see parts of the forest and share important insights about the parts that they see (though these insights are marred by their author’s failure to see the larger whole1); but Lewis shares a vision of the forest that is both deeper and more comprehensive than pretty much anyone else’s. This probably owes much to Lewis’s unique blend of talents: imaginative artist, engaging storyteller, rigorous scholar, masterful teacher, earnest seeker, etc.

We have no communication with Being, because every human nature is always midway between birth and death, offering only a dim semblance and shadow of itself, and an uncertain and feeble opinion. And if by chance you fix your thoughts on trying to grasp its essence, it will be neither more nor less than if someone tried to grasp water . . .

— Plutarch

Mere Christianity begins with an empirical argument, based on experiences that practically everyone has had, to establish the fact that we have an incipient sense of the Law of Human Nature. This Moral Law is most apparent to us when it is breached; the more flagrant the breach, the stronger our conviction that the Moral Law has, in fact, been violated. Obviously, our tendency to make judgments about violations of the Moral Law presuppose a belief in the Law itself. Pettifogging postmodern philosophers may employ sophisticated word games to quibble about this, but such arguments (which are typically dishonest because they rely on conflating mere symbols with the abstract realities those symbols represent and then constructing absurdities using ambiguities inherent in the use of symbols) fall flat in the face of real evil.

Life in a a concentration camp tore open the human soul and exposed its depths. Is it surprising that in those depths we again found human qualities which in their very nature were a mixture of good and evil? The rift dividing good and evil, which goes through all human beings, reaches into the lowest depths and becomes apparent even on the bottom of the abyss which is laid open by the concentration camp.

— Viktor E Frankl (Man’s Search for Meaning, translated by Ilse Lasch)

When we’re talking only about the kinds of minor disputes that people have all the time in polite society, it’s easy to dismiss the use of moral language as nothing more than a clever means of disguising one’s own self-interest. However, when we’re confronted with real depravity, e.g., with psychopaths trafficking and pimping young children for sex, we rightly believe that anyone who denies that such abominations really are evil is profoundly flawed as a human being, and we moreover believe that this judgment does not merely reflect our own personal preference, but rather that it is an acknowledgment of a deep and eternal reality, which would be no less real even if we were not around to pronounce our judgment about it. It is very difficult to define “The Good,” but it can be quite easy to recognize Evil when its deeds are exposed. If real Evil exists, then real Good must exist also (Lewis articulates a powerfully clear and concise argument why this must be so in Mere Christianity2).

If the whole universe has no meaning, we should never have found out that it has no meaning: just as, if there were no light in the universe and therefore no creatures with eyes, we should never know it was dark. “Dark” would be a word without meaning.

— C. S. Lewis (Mere Christianity)

The lesson I took from studying philosophy (as well as Law) is that asking the right questions and identifying the relevant issues are far more important than “knowing” the right answers. When it comes to the most important questions, reasonable minds often differ as to what the answers are. The best we can usually hope for are general principles that we can provisionally accept as True — or at the very least helpful — but knowing how to apply these principles is difficult, because the optimal application of such principles depends very much on the facts and circumstances of each specific case. For this reason, it is practically impossible to articulate a set of rules that address every possible contingency; it is difficult even to formulate a “meta-rule” for recognizing which rule should apply and resolving conflicts among those rules (I suppose Kant did as well as anyone could be expected to do with his “categorical imperative”). Aristotle noted that philosophical discourse is limited, because the terms have to “grow to meaning” within us. There’s not a flowchart or algorithm that you could mechanically apply to Life’s problems in order to resolve them all. You have to confront these perennial issues in the concrete details of your life, and then discern the eternal principles that govern Reality, and finally work out how to apply those principles beneficially to the facts of your own life.

Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, for it is God which worketh in you, both to will and to do, of his good pleasure.

— Philippians 2:12-13 (KJV)

Evil is sometimes inadvertently good in this way: it offends our moral sense, and this, in turn, makes us aware that the Law of Human Nature is encoded in the deepest part of our being. We do not understand this Law or the demands it makes of us. Flagrant violations of the Law provoke our condemnation, yet when we attempt to articulate this Law, we encounter endless difficulties. When we sketch a rough outline of the principles that comprise the Law, we are forced to acknowledge that we, too, fail to adhere to them faithfully.3 We see the corruption in the world around us and find the same corruption running through the fabric of our own lives. This strange state of affairs inspires us to ask questions. Ruminating on these questions and discussing them with others and attempting to resolve these issues in our own lives can enable us to catch fleeting glimpses of the Reality from which the Law proceeds.

Nor can man raise himself above himself and humanity; for he can see only with his own eyes, and seize only with his own grasp. He will rise, if God by exception lends him a hand; he will rise by abandoning and renouncing his own means, and letting himself be raised and uplifted by purely celestial means.

Montaigne (Apology for Raymond Sebond, translated by Donald Frame)

In our world today, Evil appears to be flourishing. Psychopaths are alarmingly bold; they’ve dropped their masks of sanity and make less effort than ever to disguise their true aims. No longer do world leaders feel the need to conceal their crimes or to justify their policies with appeals to reason or morality — however corrupt their arguments used to be, they at least used to make them, and they at least tried to make them believable. Now they tell you “2+2=5” without batting an eye. When they are caught with their hand in the cookie jar, rather than seeking to justify or excuse the theft, they simply deny the existence of both the cookies and the jar, even as they stuff a handful of cookies into their mouths right in front of you. Seeing this brazen corruption, an alarmingly large number of people have responded by going full nihilist; by lying, cheating, stealing, raping, and murdering as much as they can get away with doing. Meanwhile, the authorities ignore all the depraved criminality happening in plain sight, in order to focus all of their attention on their political enemies, whom they fear will reform the system and thereby put an end to the grifters’ gravy train.

As I searched through the literature in hundreds of fields of study, the chief thing that became apparent to me is that mankind is in the iron grip of an uncaring control system that raises him up and brings him low for its own mysterious purposes. No group, no nationality, no secret society or religion, is exempt.

—

(The Secret History of the World (and How to Get Out Alive))Undisguised Evil provokes unmistakable and un-ignorable moral outrage; and when people experience unmistakable and un-ignorable moral outrage, they are compelled to ask difficult questions; and when people ask difficult questions and are willing to wrestle with those questions long enough, they are awakened; and when people are awakened, they glimpse the Light of the True God; and the Light of the True God begins at once to break the grip that Evil has on their minds.

Jesus said, “Let him who seeks continue seeking until he finds. When he finds, he will become troubled. When he becomes troubled, he will be astonished, and he will rule over the all.”

— The Coptic Gospel of Thomas (translated by Thomas Lambdin)

Evil relies upon ignorance of the True God (True Good) for its power, but whenever Evil exercises its power openly, it awakens (at least some) people to the true nature of things, and this in turn leads those seekers to recognize that Evil is NOT the ultimate reality. Thus, Evil also relies upon keeping people ignorant of Evil; and to keep people ignorant of Evil, Evil must either (1) promote a false belief that there is no meaningful difference between “Good” and “Evil” (such that the terms “Good” and “Evil” have no real meaning), or (2) acknowledge the distinction between “Good” and “Evil” and present itself as “The Good,” in opposition to evil — i.e., masquerade as the True God. In either case, Evil must restrain itself somewhat, because if it acts too viciously, it will awaken people from their moral complacency.

My dear Wormwood . . . We are really faced with a cruel dilemma. When the humans disbelieve in our existence we lose all the pleasing results of direct terrorism and we make no magicians. On the other hand, when they believe in us, we cannot make them materialists and sceptics. At least not yet. I have great hopes that we shall learn in due time how to emotionalise and mythologise their science to such an extent that what is, in effect, a belief in us (though not under that name) will creep in while the human mind remains closed to belief in the Enemy.

— The Screwtape Letters (C.S. Lewis)

We live in a world where the Evil Power has attempted to pass itself off as the True God. Perhaps it managed to do this by creating this realm as a simulation of the true Reality, in the same way that Mark Zuckerberg might create a virtual-reality “metaverse” in which he can arrogate to himself the power and glory of a god, which is analogous to what the Gnostics believe happened with the Demiurge who created this world. Or perhaps the True God created this realm as something of a spiritual training ground where created beings like us could freely choose to develop our incipient capacity to embody Truth, Virtue, and Beauty in the concrete circumstances of our lives, but some of the created beings chose to serve themselves as gods rather than serving the True God, and in opposing the True Good, these beings became Evil and began spreading their corruption like a cancer, which is what the Christians believe happened. Or taking the Christian view in another (possibly schizoid) direction, perhaps Jesus already returned, ruled for some amount of time, but then (as provided in the timeline set forth in Revelation 20:1-10) ascended again to heaven, taking with him the saints from the first resurrection, and left the devil to run riot in this world until Jesus’s third coming and the final apocalyptic battle between Good and Evil, such that we are now living in the “era of Satanic deception.”4 Or maybe the True God is pure Consciousness, and this Consciousness has worked out the implications of every possible world in a manner similar to the way a computer program might work through countless possible moves in chess until it finds the best one, so that we are merely ideas in the Mind of God, each containing some spark of God’s consciousness but, in the context of God’s conscious vision, separate from the whole; and to return to that eternal Consciousness, we must let go of our particular identity and surrender to God, so that we can live in communion with his vision of the best of all possible worlds (which, contrary to Dr. Pangloss’s worldview in Candide, is certainly not this one!). Or perhaps the true story of our world is something else entirely. I don’t know what lies behind the appearances of this world. I know only this: that Good and Evil are meaningfully different, that Evil is presently the ascendant spiritual power in our world, that we have an incipient sense of the Moral Law, that our sense of the Moral Law is outraged by the works of Evil, that developing our sense of the Moral Law orients our attention towards the Light of the True God, and that the Light of the True God pierces through and exposes the deceptions of Evil.

It follows that this Bad Power, who is supposed to be on an equal footing with the Good Power, and to love badness in the same way as the Good Power loves goodness, is a mere bogy. In order to be bad he must have good things to want and then to pursue in the wrong way: he must have impulses which were originally good in order to be able to pervert them. But if he is bad he cannot supply himself either with good things to desire or with good impulses to pervert. He must be getting both from the Good Power. And if so, then he is not independent. He is part of the Good Power’s world: he was made either by the Good Power or by some power above them both . . . To be bad, he must exist and have intelligence and will. But existence, intelligence and will are in themselves good. Therefore he must be getting them from the Good Power: even to be bad he must borrow or steal from his opponent . . . Evil is a parasite, not an original thing.

C.S. Lewis (Mere Christianity)

Evil makes us aware of Good by highlighting its absence. Thus, Evil does do some real good. And this, to me, is proof that Evil is not the ultimate authority,5 but that it only pretends to be. Evil is a parasite, and a parasite cannot be the ultimate source of Life.

Artists vs Madmen

“Some men see things as they are and ask, ‘Why?’ I see things that never were and ask, ‘Why not?’” — Robert F. Kennedy“I agree with Robert.” — Charles Manson (or any other madman) in response to RFK’s statement. “Great wits are sure to madness near allied, and thin partitions do their bounds divide . . .

In Mere Christianity, the premises for this argument are established throughout the first part, Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe, and Lewis makes the argument explicitly in the first two chapters of the second part, What Christians Believe, as a critique of pantheism and dualism.

Tinfoil Hat Time!

Time to put on our tinfoil hats and consider an interesting “conspiracy theory” that, if true, would explain a lot about the evil and corruption we see in our world. It combines strains of Christian pre-millenialism, Gnosticism, and various notions that the history of our world has been deliberately falsified (e.g., theories like “

Good can be purely good without causing evil, but Evil cannot be purely evil without causing some good, even if only indirectly, by revealing itself as not-good and thereby triggering our incipient desire for the real Good.

This was excellent!! Thank you!

Good to see you contemplating the mystery.