“There is no political solution, to our troubled evolution,” sang Sting on the classic Police song Spirits in the Material World.1 If history teaches us anything, it is that unfathomable horrors await any society foolish enough to give power to the people who claim that such a solution is possible and that they are capable of making it happen.

As C. S. Lewis observes in Mere Christianity, “That is the key to history. Terrific energy is expended — civilisations are built up — excellent institutions devised; but each time something goes wrong. Some fatal flaw always brings the selfish and cruel people to the top and it all slides back into misery and ruin.”

In the absence of the True God, a blackpilled perspective is inevitable. It is the only honest and sober-minded assessment of our situation.

If we ever do manage to create good times for ourselves, they never last. We all know the saying: “Good times create weak men. And, weak men create hard times.” (G. Michael Hopf.)

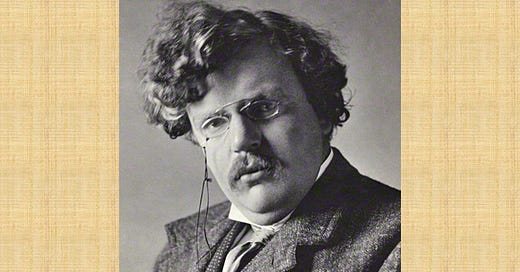

There is a passage in Chapter XVIII of G. K. Chesterton’s book The Everlasting Man that echoes a similar theme:

It was the best sort of paganism that conquered the gold of Carthage. It was the best sort of paganism that wore the laurels of Rome. It was the best thing the world had yet seen, all things considered and on any large scale, that ruled from the wall of the Grampians to the garden of the Euphrates. It was the best that conquered; it was the best that ruled; and it was the best that began to decay.

Unless this broad truth be grasped, the whole story is seen askew. Pessimism is not in being tired of evil but in being tired of good. Despair does not lie in being weary of suffering, but in being weary of joy. It is when for some reason or other the good things in a society no longer work that the society begins to decline; when its food does not feed, when its cures do not cure, when its blessings refuse to bless . . .

The limits that paganism had reached in Europe were the limits of human existence; at its best it had only reached the same limits anywhere else. The Roman stoics did not need any Chinamen to teach them stoicism. The Pythagoreans did not need any Hindus to teach them about recurrence or the simple life or the beauty of being a vegetarian. In so far as they could get these things from the East, they had already got rather too much of them from the East. The Syncretists were as convinced as Theosophists that all religions are really the same. And how else could they have extended philosophy merely by extending geography? It can hardly be proposed that they should learn a purer religion from the Aztecs or sit at the feet of the Incas of Peru. All the rest of the world was a welter of barbarism. It is essential to recognise that the Roman Empire was recognised as the highest achievement of the human race; and also as the broadest. A dreadful secret seemed to be written as in obscure hieroglyphics across those mighty works of marble and stone, those colossal amphitheatres and aqueducts. Man could do no more.

For it was not the message blazed on the Babylonian wall, that one king was found wanting or his one kingdom given to a stranger. It was no such good news as the news of invasion and conquest. There was nothing left that could conquer Rome; but there was also nothing left that could improve it. It was the strongest thing that was growing weak. It was the best thing that was going to the bad. It is necessary to insist again and again that many civilisations had met in one civilisation of the Mediterranean sea; that it was already universal with a stale and sterile universality. The peoples had pooled their resources and still there was not enough. The empires had gone into partnership and they were still bankrupt. No philosopher who was really philosophical could think anything except that, in that central sea, the wave of the world had risen to its highest, seeming to touch the stars. But the wave was already stooping; for it was only the wave of the world.

That mythology and that philosophy into which paganism has already been analysed had thus both of them been drained most literally to the dregs. If with the multiplication of magic the third department, which we have called the demons, was even increasingly active, it was never anything but destructive. There remains only the fourth element, or rather the first; that which had been in a sense forgotten because it was the first. I mean the primary and overpowering yet impalpable impression that the universe after all has one origin and one aim; and because it has an aim must have an author. What became of this great truth in the background of men’s minds, at this time, it is perhaps more difficult to determine. Some of the Stoics undoubtedly saw it more and more clearly as the clouds of mythology cleared and thinned away; and great men among them did much even to the last to lay the foundations of a concept of the moral unity of the world. The Jews still held their secret certainty of it jealously behind high fences of exclusiveness; yet it is intensely characteristic of the society and the situation that some fashionable figures, especially fashionable ladies, actually embraced Judaism. But in the case of many others I fancy there entered at this point a new negation. Atheism became really possible in that abnormal time; for atheism is abnormality. It is not merely the denial of a dogma. It is the reversal of a subconscious assumption in the soul; the sense that there is a meaning and a direction in the world it sees. Lucretius, the first evolutionist who endeavoured to substitute Evolution for God, had already dangled before men’s eyes his dance of glittering atoms, by which he conceived cosmos as created by chaos. But it was not his strong poetry or his sad philosophy, as I fancy, that made it possible for men to entertain such a vision. It was something in the sense of impotence and despair with which men shook their fists vainly at the stars, as they saw all the best work of humanity sinking slowly and helplessly into a swamp. They could easily believe that even creation itself was not a creation but a perpetual fall, when they saw that the weightiest and worthiest of all human creations was falling by its own weight. They could fancy that all the stars were falling stars; and that the very pillars of their own solemn porticos were bowed under a sort of gradual Deluge. To men in that mood there was a reason for atheism that is in some sense reasonable. Mythology might fade and philosophy might stiffen; but if behind these things there was a reality, surely that reality might have sustained things as they sank. There was no God; if there had been a God, surely this was the very moment when He would have moved and saved the world.

Well, I think as we look at the state of the West today, at the crumbling ruins of a once great civilization, we find ourselves in exactly the same predicament. Or to revisit the C. S. Lewis quote, once again we see that this same fatal flaw has brought the selfish and cruel people to the top and that it has all been sliding back into misery and ruin for the past several years.

I do believe there is a possibility of things being put right and of real reforms that cleanse our societies of the cancerous evil that has turned the West into a culture of death, but it requires us and our leaders to connect with the True God. Will that happen?

In light of the crossroads at which our civilization now stands, where ruin (whether gradually or suddenly) lies before us unless we conscientiously change course (and agree to make the difficult choices required for that), I think the warnings and insights of G. K. Chesterton are more relevant and needed than ever before. The man was truly a prophet, seeing clearly a century (or more) ago the kinds of things that have only lately become obvious to many of us. He saw the infernal spirit whose presence and plans tie together all the disparate threads of insanity that have afflicted the West throughout our lifetimes. And he saw the possibility that the True God might intervene and save us.

In this new podcast series, Paging the Everlasting Man, I will read G. K. Chesterton’s books and essays and then give commentary on what I have read. This is the introductory episode. This series will have be separate from normal A Ghost in the Machine podcast episodes, and I believe that will mean a different RSS feed as well. I apologize for the inconvenience of subscribing to a separate podcast, but I think it will avoid confusion if I keep my readings of Chesterton separate from the ordinary podcast episodes I do (which I also plan to continue). Much of this series will probably be behind a paywall (so far I have done some written posts for paid subscribers, but have not given them any exclusive audio content). If you are interested in a paid subscription, you can use one of the buttons below to get a discount. You can copy your private RSS feed that Substack will give you and paste it into an app or streaming service that is compatible with private feeds, or you can listen to episodes in the browser or Substack app.

This is the introductory episode. I will (shortly) publish my reading of the first chapter of Chesterton’s 1905 book Heretics,2 so you can see if this is something you would be interested in listening to. And if it’s not, no problem. Regular posts and podcast episodes will continue. If you do join me on these readings — I plan to at least cover Heretics (which we’re starting with), Orthodoxy, and The Everlasting Man — I think this will be a worthwhile journey.

A Road Map for the First Part of the Series

Here is the table of contents for Heretics. Each one will be a separate episode, with the reading of the chapter first and my commentary second.

1. Introductory Remarks on the Importance of Orthodoxy

3. On Mr. Rudyard Kipling and Making the World Small

5. Mr. H. G. Wells and the Giants

6. Christmas and the Esthetes

7. Omar and the Sacred Vine

8. The Mildness of the Yellow Press

9. The Moods of Mr. George Moore

10. On Sandals and Simplicity

11. Science and the Savages

12. Paganism and Mr. Lowes Dickinson

13. Celts and Celtophiles

14. On Certain Modern Writers and the Institution of the Family

15. On Smart Novelists and the Smart Set

16. On Mr. McCabe and a Divine Frivolity

17. On the Wit of Whistler

18. The Fallacy of the Young Nation

19. Slum Novelists and the Slums

20. Concluding Remarks on the Importance of Orthodoxy

As I release new episodes, I will add hyperlinks to each chapter title.

Embedded music video (from YouTube) for the Police song Spirits in the Material World:

Heretics Chapter One: Introductory Remarks on the Importance of Orthodoxy

In this episode, I read the first chapter of G. K. Chesterton’s book Heretics and then give some commentary. (If you missed the introductory episode, you can listen to it «here».) As mentioned previously, this is a separate series from my normal podcast, which I will still continue to do while doing these readings.

Share this post