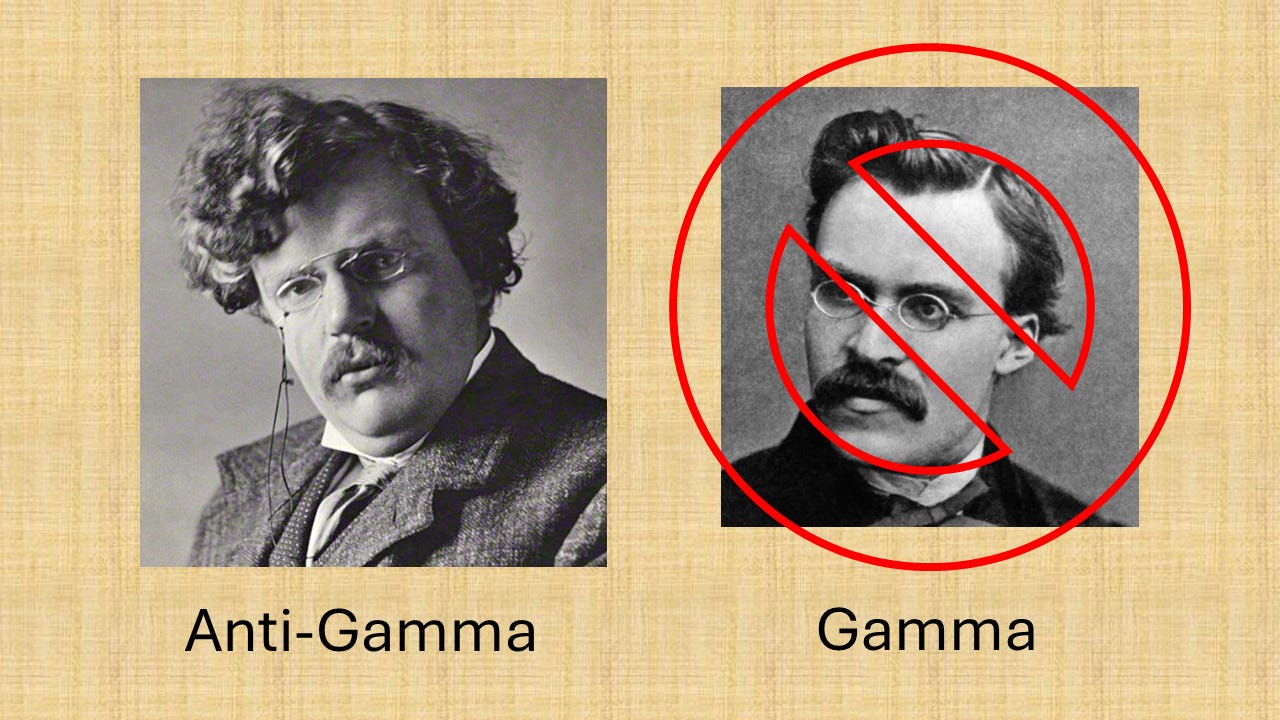

If Friedrich Nietzsche is the “Gamma Philosopher,” as Vox Day called him in a recent post,1 then G K Chesterton is the Anti-Gamma Philosopher. This isn’t to say that Chesterton was an Alpha or Sigma2 — he definitely wasn’t. To all appearances, he was not especially virile; he was nerdy, unathletic, and could be a bit slovenly in his everyday appearance; he definitely wasn’t handsome or any kind of ladies’ man; and although he eventually married, his wife was a thoroughly plain jane rather than any kind of beauty queen. Chesterton clearly had gamma potential, but he appears to have ended up a good-natured, well-adjusted, and highly successful man. For that reason alone, Gammas and potential Gammas should read him.

How did Chesterton avoid becoming a Gamma, when he didn’t lift, didn’t become a deadly MMA fighter with an intimidating aura, didn’t become the captain of his school’s football team with the prettiest cheerleaders all vying for his attention, and didn’t become a skilled pickup artist with a long list of enviable conquests? I think his secret lies in his witty observation, “Angels can fly, because they take themselves lightly.”

The tl;dl (Too Long; Didn’t Listen) of this episode is that Chesterton took himself lightly; Nietzsche did not. You could easily imagine Chesterton being roasted by a panel of comedians and laughing more than anyone else. You could imagine Chesterton thoroughly enjoying the jokes being made at his expense and then topping them, both with self-deprecating humor and by giving as well as he got and roasting the very people who were roasting him, and it would have all been done in a spirit of expansive cheer and friendly fun. Chesterton had a quick and nimble wit and a jovial spirit and could have won any audience over to his side. He was not a gamma-esque “secret king,” so he would have been free of the need for others to give him the honor and deference due a king.

You can imagine Chesterton rolling with the punches and having a deep belly laugh at his own expense. You can hardly imagine Nietzsche doing the same. Nietzsche held too many grudges and nursed too many resentments and took himself far too seriously to ever truly let himself go and cheerfully laugh even when he was the butt of the joke. Nietzsche was too smart and thought too highly of himself to live a normal Delta life doing normal Delta things. He was the “secret king” incarnate, and he seriously “believed in himself” like the maniac Chesterton describes in the second chapter of Orthodoxy (in which he recounts a conversation with a publisher friend of his about whether it is good to believe in oneself):

I said to him, "Shall I tell you where the men are who believe most in themselves? For I can tell you. I know of men who believe in themselves more colossally than Napoleon or Caesar. I know where flames the fixed star of certainty and success. I can guide you to the thrones of the Super-men. The men who really believe in themselves are all in lunatic asylums." He said mildly that there were a good many men after all who believed in themselves and who were not in lunatic asylums. "Yes, there are," I retorted, "and you of all men ought to know them. That drunken poet from whom you would not take a dreary tragedy, he believed in himself. That elderly minister with an epic from whom you were hiding in a back room, he believed in himself. If you consulted your business experience instead of your ugly individualistic philosophy, you would know that believing in himself is one of the commonest signs of a rotter. Actors who can't act believe in themselves; and debtors who won't pay. It would be much truer to say that a man will certainly fail, because he believes in himself. Complete self-confidence is not merely a sin; complete self-confidence is a weakness.3

This passage cuts straight to the heart of the matter. “I can guide you to the thrones of the Super-men.” And what secret kings would Chesterton and his friend have found sitting there, atop these “thrones of the Super-men,” in the imaginary castles nestled in the dismal corners of a dilapidated insane asylum? Nietzsche and his ilk.

What answer does Chesterton give to this solipsistic monomania? Not logical arguments, where the flawed premises of self-worship and bitter resentment are left intact, but rather a complete shift in attitude and perspective: renouncing one’s secret kingship and embracing one’s status as a human being, subject to the laws of Nature and Nature’s God.

The madman's explanation of a thing is always complete, and often in a purely rational sense satisfactory. Or, to speak more strictly, the insane explanation, if not conclusive, is at least unanswerable; this may be observed specially in the two or three commonest kinds of madness. If a man says (for instance) that men have a conspiracy against him, you cannot dispute it except by saying that all the men deny that they are conspirators; which is exactly what conspirators would do. His explanation covers the facts as much as yours. Or if a man says that he is the rightful King of England, it is no complete answer to say that the existing authorities call him mad; for if he were King of England that might be the wisest thing for the existing authorities to do. Or if a man says that he is Jesus Christ, it is no answer to tell him that the world denies his divinity; for the world denied Christ's.

Nevertheless he is wrong. But if we attempt to trace his error in exact terms, we shall not find it quite so easy as we had supposed. Perhaps the nearest we can get to expressing it is to say this: that his mind moves in a perfect but narrow circle. A small circle is quite as infinite as a large circle; but, though it is quite as infinite, it is not so large. In the same way the insane explanation is quite as complete as the sane one, but it is not so large. A bullet is quite as round as the world, but it is not the world. There is such a thing as a narrow universality; there is such a thing as a small and cramped eternity; you may see it in many modern religions. Now, speaking quite externally and empirically, we may say that the strongest and most unmistakable MARK of madness is this combination between a logical completeness and a spiritual contraction. The lunatic's theory explains a large number of things, but it does not explain them in a large way. I mean that if you or I were dealing with a mind that was growing morbid, we should be chiefly concerned not so much to give it arguments as to give it air, to convince it that there was something cleaner and cooler outside the suffocation of a single argument. Suppose, for instance, it were the first case that I took as typical; suppose it were the case of a man who accused everybody of conspiring against him. If we could express our deepest feelings of protest and appeal against this obsession, I suppose we should say something like this: "Oh, I admit that you have your case and have it by heart, and that many things do fit into other things as you say. I admit that your explanation explains a great deal; but what a great deal it leaves out! Are there no other stories in the world except yours; and are all men busy with your business? Suppose we grant the details; perhaps when the man in the street did not seem to see you it was only his cunning; perhaps when the policeman asked you your name it was only because he knew it already. But how much happier you would be if you only knew that these people cared nothing about you! How much larger your life would be if your self could become smaller in it; if you could really look at other men with common curiosity and pleasure; if you could see them walking as they are in their sunny selfishness and their virile indifference! You would begin to be interested in them, because they were not interested in you. You would break out of this tiny and tawdry theatre in which your own little plot is always being played, and you would find yourself under a freer sky, in a street full of splendid strangers." Or suppose it were the second case of madness, that of a man who claims the crown, your impulse would be to answer, "All right! Perhaps you know that you are the King of England; but why do you care? Make one magnificent effort and you will be a human being and look down on all the kings of the earth." Or it might be the third case, of the madman who called himself Christ. If we said what we felt, we should say, "So you are the Creator and Redeemer of the world: but what a small world it must be! What a little heaven you must inhabit, with angels no bigger than butterflies! How sad it must be to be God; and an inadequate God! Is there really no life fuller and no love more marvellous than yours; and is it really in your small and painful pity that all flesh must put its faith? How much happier you would be, how much more of you there would be, if the hammer of a higher God could smash your small cosmos, scattering the stars like spangles, and leave you in the open, free like other men to look up as well as down!"4

(Note: for a different perspective on Nietzsche, check out

’s excellent post The Prophet of the Twentieth Century.5)And if you want to tell me why I got your favorite philosopher all wrong and what a Gamma I obviously am, kindly click on this button …

… And let me know all about it in the comment section.

And whether you love Nietzsche or hate him, or (and Nietzsche would find this last possibility most intolerable of all) whether you really don’t care one way or the other about him or his philosophy, be sure to read G.K. Chesterton, especially his books Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. If you’re listening on a podcast app or streaming platform, check out the substack page for this episode to get embedded content (which usually doesn’t display properly on third-party sites).

Alpha, Sigma, Delta, Gamma, etc. are categories in Vox Day’s articulation of the Human Socio-Sexual Hierarchy:

Excerpt from Chapter Two of G.K. Chesterton’s 1908 book Orthodoxy. (Emphasis added.)

Excerpt from Chapter Two of G.K. Chesterton’s 1908 book Orthodoxy. (Emphasis added.)

Share this post